THE 1973 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC STRIKE TOUR

by Gabriel Banat

August 1973. On the way home from our family vacation near Barcelona, I was invited to lunch in Madrid with concert manager Alfonso Aijon. He asked me whom to approach about arranging a tour of the NY Philharmonic in Spain. I explained that might be difficult, as their season starts after our regular season has already begun but, as he insisted, I gave him Philharmonic President Carlos Moseley’s address.

Early that September, while on tour with the orchestra in Lexington, Kentucky, I received a copy of Mr. Aijon’s letter. It began with, “at violinist Gabriel Banat’s suggestion…” and contained details for a possible tour of six concerts. I read it quickly and put it in my pocket, annoyed to be mentioned by name. The next day we heard from our negotiating committee in New York. Talks were stalled and, despite the threat of a double-digit inflation, with no improvement on wages, we might go on strike. To my surprise, though I had only been on tenure a short while, I was chosen to serve on our 16-member “Steering Committee.”

Back in New York, we found a huge banner draped over the façade of our hall displaying its new name: “Avery Fisher Hall.” Due to the dismal acoustics of Philharmonic Hall, many artists and orchestras were returning to Carnegie. Some of my senior colleagues were upset by the fact that, to insure the move to Lincoln Center, Amyas Ames, on the Board of the Philharmonic and co-incidentally chairman of the board of Lincoln Center, declined to buy Carnegie Hall offered to the orchestra for five million dollars. In view of the enormous cost of a massive remake of Philharmonic Hall, Mr. Fisher’s offer of a gift of eight million dollars to the orchestra came at just the right time. In fact, the administration spent several weeks trying to convince Mr. Fisher to donate his gift instead to Lincoln Center. Management’s version was that his gift was for the maintenance of the hall, but the virtually simultaneous announcement of plans for its reconstruction suggested to my fellow musicians that it was meant to cover the cost of rebuilding the hall. Many of us including our negotiating committee believed that, since Mr. Fisher’s gift fell short of the cost of the overhaul, the difference of over four million dollars was the cause of the hardened attitude of the management.

September 25: the strike was on. The steering committee designated me “Impresario” pro tem. of the orchestra. After 25 years of a solo career, I welcomed the opportunity of doing something for my 105 fellow musicians. My Performance Committee included Lenny Hindel, Larry Newland, Lou Robbins (librarian) and Morris “Arnie” Lang. Dick Simon and Mati Braun were kept busy finding venues for giving chamber music concerts in the area. We decided to start with a concert for the benefit of the orchestra. Lenny Hindell tried to get Carnegie Hall, but was told that it was fully booked. Bypassing the office I called Isaac Stern, the savior of Carnegie Hall, who agreed to let us have it for our concert, pretending that its rental fee of $3000 would be paid by an ”anonymous donor” (which I suspected was Isaac, himself). I thought that it was only fitting to ask Pierre Boulez, our Music Director, to conduct the concert. My colleagues reluctantly agreed, certain that he would have to decline. Accompanied by our first violist, Sol Greitzer as my witness, I met Mr. Boulez at the Lincoln Center Library. To our surprise, he promptly reached for his diary, and offering to fly back from London just for those two days, said he would do it. When I suggested that management might object, reverting to his former firebrand self, he said “ But why would they? I would be acting as your colleague, not as your Music Director.” Nevertheless, he asked us to return later that afternoon, after he informed (sic) the board. We did so at five o’clock, but found him visibly shaken. He told us, “The chairman of the board said, ‘If you do this, your contract isn’t worth toilet paper.‘”

We had a hard time finding a conductor (some were busy, others were worried about repercussions). Accompanied this time by French hornist “Dini” De Intinis, we approached Leon Barzin. He said he would, as his mother-in-law, the late Mrs. Merriweather, had just endowed his National Orchestral Society with 55 million dollars, so he “didn’t give a hoot about repercussions.” It rained hard the night of the concert, but a sizable audience applauded enthusiastically as the orchestra, led by Associate Concertmaster Frank Gullino, marched out as one and stood there together savoring the minutes-long applause. The soloists on that special night were three of our own first chair men: Julius Baker with a Mozart flute concerto, John Cerminaro with Strauss’ horn concerto # 1, and Lorne Monroe playing Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations. We started with the overture to Benvenuto Cellini by Berlioz and ended with Ravel’s La Valse. Leon Barzin conducted with empathy and brio. Our take was $10,000, net.

Some of the members on the board were furious about the concert. With Isaac Stern away on tour, his wife, Vera, received a number of nasty calls. One confused board lady called Isaac “a strike-breaker.” After the concert I found it difficult to organize another. My phone calls were not returned. Max Arons, our union chief, called it a “secondary boycott.”

With the strike in its seventh week, the negotiations were still deadlocked. It was turning cold and on the picket line where we all took turns the hostile comments by people passing by were beginning to outnumber the nice ones. A day or two after the Carnegie Hall Concert, while marching around carrying a board, a minor member of the management came up to me and held out his hand. Pleasantly surprised, I was extending mine when instead of shaking it he dropped a nickel in my palm. His gleeful laughter reminded me of an item in that morning’s Times: a new undersea cable reduced the cost of a call to the Continent to only ten dollars. When I got home I re-read Alfonso Aijon’s letter to Carlos Moseley, picked up the phone and called Ibermusica in Madrid. “Are you still interested in a tour by the New York Philharmonic?” I asked Aijon. He said that though his letter was unanswered (Carlos Moseley was in the hospital with a heart attack), he was definitely interested. I wondered if he could have us very soon, within ten days, no more? “Yes, I think so”, he said, “but what about your season…” “This time it’s different,” I replied, “er…we are on strike.” There was a brief pause, then, “It could be done,” he said, “I will call you back after I consult our Minister of Culture.” “Go ahead,” I replied, “I too must discuss this with our Committee.”

My colleagues of the Negotiating Committee were ecstatic! I was the man of the hour! They wanted me to go right head and make it happen. As by then Sr. Aijon had the approval of his Minister, we reaffirmed the terms contained in his letter to Moseley: $20,000 per concert, plus travel and per diem, hotel accommodations and air fare. He also accepted my condition that the fees for the concerts should be paid in advance into an escrow account in New York and released via telex after each performance. Since our first concert in Madrid would take place under the patronage of Sra. Carmen Polo de Franco, (wife of the Caudillo, Francisco Franco) and the Infanta Sophia, the present Queen of Spain, the resulting combination was a veritable paradox: an orchestra on strike touring Spain under the auspices of its fascist dictator.

Meanwhile, with our Negotiating Committee and management still at an impasse, I came under increased pressure to get on with our Iberian tour. Concert dates, programs, conductors, accommodations were all negotiated via my home telephone, operating day and night until dawn, given the time lag with Europe. To save money, we tried to communicate through July Baker’s ham radio and a helpful operator somewhere in Spain, but found the telex machine at Truvynil in Brooklyn where my wife, Rosette worked as a stylist, more reliable. A clerk in the factory would collect the messages received overnight and read them to me early in the morning. I would then telex back or phone if the matter was urgent. Trouble developed in Lisbon, the first stop on our tour, until Julius Bloom––who managed Carnegie Hall for Isaac Stern and who, with the latter’s approval, was a great help to us throughout–– helped me resolve it. Ever more pressing were our travel arrangements. We were already a day late paying for the 14-day reduced group charter rates with TWA. I managed somehow to have the tickets backdated, but now found myself blindsided by some of my colleagues on the Committee. While they continued to urge me to forge ahead, three of its five members, cynically viewing the tour as just another bargaining chip, was telling the management–––and the press–– that we would return to work the instant a contract would be signed. Had I already paid for the tickets, Aijon’s management could lose their five figure investment. Warned about the danger by the other two members of the Committee, I asked for a plenary meeting of the orchestra. It took place at the Korean church on West 66th street and was attended by eighty-one members of the orchestra, the leaders of Local 802 and its lawyer. A week of being constantly on the telephone made me lose my voice, but I somehow managed to get across to my assembled colleagues that we have reached the point of no return. Ibermusica, Mr. Aijon’s management, was sending us $35,000 to pay for our airfare; we must not betray their trust in us by taking their money while negotiating to return to work before going to Spain. I therefore was asking them to vote to set aside the ten days for the tour, or else instruct me to call it off then and there. The result of the vote was 80 in favor of the tour with one abstention. Local 802 agreed to act as our representatives and sign a contract in our name with Ibermusica.

Mr. Aijon’s brother-in-law, Hel Bruno, was already in New York with the money for our group airfare and about to hand it to TWA. But when I learned (from the New York Times, no less) that our Committee, ignoring the vote by the orchestra, continued to assure management that we would swap the tour for a viable contract, I had Bruno, who understood immediately what was at stake, check out of the Sheraton, and brought him home with me to Westchester. I then informed the Committee that, on my advice, Sr. Bruno went back to Spain. Later that day the three holdouts on the Committee begged me to get him back. I said I would try if they would agree to a deadline, five o’clock the following afternoon when, should they fail to reach an agreement with management, they must be the first to sign a legally binding contract with Ibermusica to go on tour. I borrowed Continental Ore Company’s sumptuous Park Avenue boardroom from my friend, Louis Lipton, its president. There, with bassist Orin O’Brian typing the contract with Ibermusica dictated to her by a lawyer, also borrowed from Continental, we waited for the committee to show up. Gino Sambuco and Jon Deak, who first warned me about the troika’s intrigues, arrived promptly at five o’clock and saying that as there was still no agreement, the others were coming soon. It was 5:45 by the time they arrived, looking downhearted but eager to sign. Sensing the negative attitude of the troika about the tour, the management believe that it was just a bluff. A hundred musicians going on tour with just two weeks’ notice? It was too fantastic to believe! It certainly was. Alas, though Local 802, on the belated advice of its lawyer, withdrew their offer to sign our contract, thanks to our telephone committee’s heroic efforts, ninety five of my Philharmonic colleagues came to the union’s headquarters at midnight on a Sunday, (Nov 1) lining up to cover the four blank pages attached to the contract with their individual signatures. It was a scene right out of the Hollywood movie “100 Men and Girl” with Deanna Durbin and Leopold Stokowski which, having seen it as a boy, first gave me the notion that we, the musicians, could go it alone.

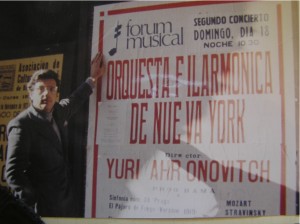

What our tour still needed was a conductor. Fear of being blacklisted caused some of the two score maestros we polled to decline. Others were busy elsewhere. Stokowski, 93, was recording in London, still! In the end it was Aijon who found one for us. Yuri Ahronowitch was formerly the conductor of the Moscow Radio-TV orchestra. Released from prison were he was incarcerated by the Soviet for “Zionist sympathies,” he immigrated to Israel, and was conducting in Western Europe. He recently took part in Israel’s Yom Kippur War. Now, refusing to make cuts in Tschaikovski’s Pique Dame at the Swedish National Opera, he resigned, making himself available to us. None of us had even heard of him and, when I finally spotted him at the airport, his battered suitcase and shabby corduroy cape did not exactly fill me with confidence. Neither did his request that I buy him a baton, the longest I could find. The next morning, looking for him at the St. Regis to take him to the rehearsal, he was not in his room, in the lobby, or in the coffee shop. I finally spotted him outside, at the corner of Madison Avenue, peering into a shop window. Pointing at a shirt within, he said he could not conduct such a great orchestra as the New York Philharmonic in his old sweatshirt. He spoke no English but, communicating in a mixture of Yiddish and German, I assured him that casual dress was all the rage in America, and took him in a cab to Carnegie, lent for our rehearsals by Isaac. My colleagues, tuning up, scrutinized my scruffy looking maestro with a dash more than their usual skepticism. As the little Russian raised his long baton, I worried about being lynched should he fail to deliver the goods. But when the first chords of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth rang out with the brass sounding firm yet warm and mellow as always in that venerable old hall, I knew that we were in the hands of a real conductor. Overwhelmed and immensely relieved, I had to leave the stage and hide in the men’s room for a few minutes to regain control over my emotions.

In the meantime TWA, our original airline, went out on strike. Had we paid for our tickets in time, Pan Am would have honored them. Now I had no choice but to go to Iberia. There, in its Fifth Avenue office behind a big desk sat–– the “Godfather.” Sounding just like Marlon Brando, he growled, “Why didn’t you come to see me before?” Having missed the deadline for the cheaper fare, our tour cost Ibermusica an additional $10,000. Our sendoff from the newly baptized Avery Fisher Hall was truly spectacular. The Union, perhaps to expiate its timidity, sent us off in style with a great brass band playing marches while, with little red bows tied to our instruments, we boarded the busses taking us to the airport. A number of faces peered down at the improbable scene from management’s sixth floor office windows. I wondered if the joker who put that nickel in my palm was among them.

In the last minute, unbeknownst to me, two members of my committee were arbitrarily replaced by Di Intinis from the Committee and Ralph Mendelson, grey eminence of the latter. I was being watched. Now, true to Iberia’s reputation it gave our plane to another group. Worse luck, the door of the substitute, a Boeing 707, was too narrow for the large instruments, the basses, timpani and the harp. We were already aboard when I was told that the large instruments would have to on another airplane. I asked to see the captain, told him in Spanish that he must not leave until we made sure that those instruments were in fact on that plane, then sent bassist Johnny Shaeffer, normally our assistant personnel manager, to the other gate to make sure that they were. Dini, who had no Spanish, promptly accused me of sabotaging the tour! Later, in mid ocean, told by the crew that we would land in Madrid (to refuel), Dini once again accused me, this time of incompetence. Before I could defend myself, on a signal by Ralph, that I caught, he moved up and, with his substantial belly, pushed me against the bulkhead. Feeling his chin thrust into my face, giddy from two weeks of sleeplessness, I just bit down on it. Once on the ground in Madrid, I told him I was sorry. Later Aijon told me that after we left New York someone on the Committee called him to say that once in Spain, they were replacing me with De Intinis. Aijon, whose management nearly went under because of their machinations, replied that, in that case the orchestra might as well take the next plane back because he would only deal with Banat. I could just imagine Hel Bruno hearing that the “peasant,” who was always chewing on a toothpick, was to take charge of the tour.

Before leaving New York, we received letters from two law firms – the one in Spanish was from the Rockefellers’ permanent representatives in Madrid–– threatening to sue us and Ibermusica if we billed ourselves as “The New York Philharmonic.” Nevertheless, though in Lisbon we were called “A Hundred Professors of the New York Philharmonic” in Spain, where they dropped the “Professors”, the government’s reaction was, ”Let them.” They never did.

At 4: 30 in the morning following our second spectacular concert in Lisbon, with Aijon’s wife, Kristina Bruno driving, Don Whyte and I set out for Madrid to check on our hotel reservations. A good thing too, because the list of the musicians received by the hotel used only initials rather than first names and some of our women colleagues would have been sharing a room with a guy. It took some time before we got them to separate mismatched couples and reallocate the rooms. By then the orchestra’s arrival from Lisbon was seriously overdue. As it turned out, they were still stuck at Lisbon’s airport; Iberia did it again! The 737 it sent for them could not accommodate the larger instruments. Unfortunately, my plea to Ibermusica to please check with Iberia every two hours was thought to be exagerated. A frantic search for a replacement aircraft was fruitless. Although concerts in Spain started at 10:30 p.m., still, time was getting short. Finally, around 4 p.m. Aijon’s brother-in-law, a colonel and commander of Barajas, Madrid’s main airport, on his way home from a holiday, stopped by the airport. Told that Alfonso was desperate to get the orchestra to Madrid, he sent a huge Boeing 747, the only craft then available, to fetch them from Lisbon (at Ibermusica’s expense). They arrived exhausted and very cross with me, complaining about the cold jamon y queso sandwiches they had to gobble down sitting in their overcoats before boarding the buses to the concert. I can still hear my friend, the oboist Al Golzer saying, “Hey Gabe, no more such favors, OK?”

The audience in the vast Palacio de Congresos, waiting for the concert to begin at 10: 30, was informed that there would be a delay of half an hour. Knowing they should multiply that by two, some people invaded the bar, others, including Sra. Franco, went for a stroll around the block. The seven cabinet ministers present started an ad hoc cabinet meeting upstairs. Although it was eleven o’clock when the orchestra arrived at the hall, both the orchestra and the audience had to wait another half hour while the cabinet wrapped up their business. The concert, which began at 11:30, was televised, but fortunately on tape. In spite of the horrendous day, Lorne Munroe gave an outstanding performance of the Dvorak concerto. In fact we all outdid ourselves that night. At last, around three o’clock in the morning, everyone was stashed away in their rooms at the hotel Equestre. Everyone except two busy guys left without a room: Walter Botti, the bassist, our volunteer “baggage master,” and yours truly. Happily, my call to Aijon’s home got each of us a deluxe suite in the five star Palace.

The rest of the tour went smoothly, with our two concerts in Madrid, followed by two (including an additional second one) in Barcelona, with Yuri conducting a sensational Shostakovitch Seventh, and Lorne magnificent in Dvorak’s cello concerto. After his encore, El Cant Dels Ocells––a Catalan traditional melody arranged by Casals and dedicated by Lorne to his memory on this, the first anniversary of his death––the predominantly Catalan audience erupted in cheers. Following the symphony they had us take sixteen curtain calls! The two remaining concerts in the Canary Islands seemed almost restful, except for our principal second violin, Marc Ginsberg, who walked into a glass door and needed a few stitches on his forehead. But for Dini’s chin, it was the only injury of our self-managed tour. The good news was that, instead of some sponsor spending half a million, our tour of eight concerts earned 75,000, tax free dollars (for our strike fund) help for some overdue rent and mortgage payments.

Back home at Kennedy airport, we were met by some of our local TV cameras. Asked for our reasons for going on tour, I for one said that it was to prove that the real principals of the New York Philharmonic are the musicians of the orchestra, not the “Society” or the management. I felt that, as heirs to the musical tradition of generations of our predecessors over the 130-year history of the Philharmonic, an orchestra like ours is unique and irreplaceable. I wish this could have been as clear to all my colleagues as it was to me. But some of us, including the members of our Negotiating Committee who had stayed behind and missed the sense of freedom and pride we felt on tour, were all too eager to sign a contract that, had we held out at least over the week-end, might have been more favorable. Nevertheless, I believe that the point we made did have some effect on our subsequent contract negotiations. I fervently hoped that there would never again be need for another strike.

On my return from Spain I received calls from the committee chairmen of the five major American orchestras, beginning with Ralph Gomberg, first oboist of the Boston Symphony and brother of our own Harold Gomberg. Facing negotiations, they all hoped I could tell them how to organize a strike tour in Spain or elsewhere in Europe. I regretted having to tell them that it was no longer possible. After the problems we caused Ibermusica, no European manager would risk handling an American orchestra while on strike.

The combination of responsibility without authority earned me a few enemies both among my colleagues and, naturally, the management. Reacting to an overtly vengeful order by Harold Lawrence, the new managing director, I was obliged to call Local 802’s president, Max Arons, a union leader of the old school, who warned him to “leave our boy alone, or you shall not last out the year!” which actually turned out to be true. In time, as our Spanish tour morphed into legend among musicians, indeed for over a decade every time the entire orchestra met in the clubroom to discuss the terms of a new contract, someone would shout, “Hey, Gaby! How about another tour in Spain?” Still, or perhaps because of that, our management pretended that it never happened. This became abundantly clear fifteen years after our strike tour when the orchestra was about to return to Spain, and the management’s communiqué in the New York Times claimed that it was our first visit to that country. Happily, most of my colleagues did remember. Five years after my retirement from the Philharmonic, I received a photo. Taken in Madrid it showed Alfonso Aijon surrounded by a group of veterans of that first tour. According to a note, it celebrated the 25th anniversary of our tour by raising a glass of good Rioja in my honor.

Alas, though we kept asking our management to invite Yuri Ahronovitch to conduct the Philharmonic in New York, the answer was always no. Many years later, when Yuri brought his Stockholm Philharmonic to Carnegie Hall and I went to see him, he gave me a Russian bear hug, but his pretty wife, a former sergeant in the Israeli army, blamed me for “being responsible for my husband having been blacklisted by American orchestras.” I regretted that she gave me no chance to explain that it was not I, but Alfonso Aijon who had found him for us.

NOTE: I originally deposited a file containing the documents of the tour with the New York Philharmonic Archives. Told that it was “restricted,” including to John Canarina, the author of “The History of the New York Philharmonic from Bernstein to Maazel,“ I moved the documents, including a letter to me from Pierre Boulez, to the Music Division of the Library and Museum of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.